Summary

Key questions

- Why is energy poverty not just called ‘income poverty’?

- What are the best ways to detect, measure, monitor, and address energy poverty?

This policy brief discusses the measuring and monitoring energy poverty in the EU Member States.

Lead authors: Vlatka Kos Grabar Robina, Bruno Židov, Robert Fabek (EIHP)

Reviewers: Didier Bosseboeuf (ADEME), Wolfgang Eichhammer (Fraunhofer ISI)

Introduction

Energy poverty is a situation when persons struggle to keep their home adequately warm in winter and cool in summer. They struggle to pay electricity bills, usually live in poorly lit homes, or are unable to use domestic appliances as needed. They may lack – in part or fully – access to the power grid, becoming socially excluded and suffering negative consequen¬ces as a result.

Behind these relatively easy to describe circumstances, however, lie a series of complex ques¬tions. Why is energy poverty not just called ‘income poverty’? Who is most affected by this condition and how? Are urban or rural dwellers more vulnerable, and in what manner does it vary across different regions and countries? What are the best ways to detect, measure, monitor, and address the problem?

Energy poverty is commonly defined as the inability to secure adequate levels of energy services in the home. This definition has three interlinked elements that need further explanation.

First, secure means that there may be multiple reasons why a household cannot attain the energy it needs. This may involve not being able to pay for the required energy (energy affordability) or lacking the necessary supply infrastructure (energy access). Energy affordability challenges are more common in developed countries, whereas energy access is frequently an issue in the developing world. The access element involves not only electricity grids but also district heating and gas.

Second, the adequate level of domestic energy involves both a material and social minimum. The material minimum is a level of domestic energy services below which living in a home is unhealthy, as cited in most academic papers on the subject, which generally advocates as a temperature of 21°C in occupied rooms, and 18 °C in bedrooms. The social minimum is a level of domestic energy below which a household has problems in undertaking customs and practices that define membership in a society. These households are living in a home that is too cold, too warm, inadequately lit, or imposing limitations on appliance use, with well-known negative effects on personal wellbeing and social participation.

Third, energy services delivered to home are bene-fits contributing to human wellbeing. Energy services include activities such as heat and cooling of living spaces, water heating, lighting, and powering of appli¬an¬ces. Energy services normally satisfy specific human needs, require human involvement for utili¬zation, and rely on energy conversion inside the boun¬daries of the home. All this depends on the energy efficiency of domestic installations and infra¬struc¬¬ture, such as the building envelope (walls, win¬dows, doors, roofs), heating systems, and appliances.

Causes, consequences and patterns of energy poverty

Despite being dependent on local situations, the causes of energy poverty are relatively well known. In developed countries, a household is more likely to be energy poor if it has a lower-than-average income, lives in an energy inefficient home, has higher-than-average energy needs and is unable to use forms of energy best suited to its needs due to technical, legal, or economic barriers.

The consequences of energy poverty are primarily poor health outcomes: prolonged exposure to cold air, moisture or condensation leads to adverse consequences on respiratory and circulatory systems and in turn leads to increased mortality and morbidity during winter (as well as summer heatwaves in some situations). Energy poverty also has severe impact on mental health and limits educational and economic out¬comes. The use of polluting fuels among energy-poor households is also associated with air pollution.

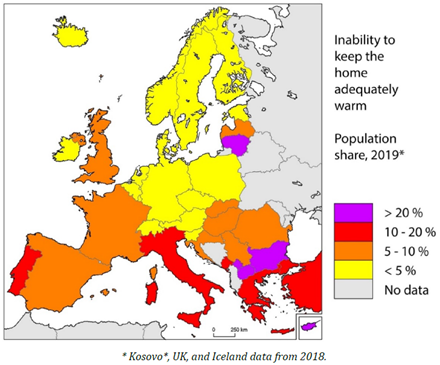

Energy poverty occupies a specific geographical region in Europe and beyond. The values for some of the most common indicators used to detect these problems are highest in South-eastern European states, as well as several other Southern, Central, and Eastern European states (Figure 1). In essence, an energy poverty ‘divide’ exists between this group of countries, on the one hand, and Northern and Western European states, on the other. In countries where energy poverty rates are higher, this is due to a combination of circumstances: increases in energy prices, high levels of income poverty, low quality and inefficient housing, lack of necessary energy infrastructure, and additional social vulnerabilities (gender, disability, ethnicity).

Figure 1: The energy poverty divide in Europe

Source: S. Bouzarovski, H. Thomson, and M. Cornelis, “Confronting Energy Poverty in Europe: A Research and Policy Agenda,” Energies, vol. 14, no. 4, Art. no. 4, Jan. 2021, doi: 10.3390/en14040858

There also exist differences among and within countries. Rural areas are particularly vulnerable as people living there usually inhabit lower-quality housing and are often forced to rely on polluting fossil fuels (such as fuelwood and coal) for heating, especially in the South-eastern European countries. In urban areas, residents of large housing estates equipped with district heating may often find it expensive to pay for heating and hot water.

Definition and measuring of energy poverty in selected EU countries

It seems that an agreed definition of energy poverty has proven to be elusive and is contested. Much of the early research into energy poverty within the EU has been aimed at providing a definition – with early papers using the term fuel poverty as opposed to energy poverty. These concepts have different origins and different focuses. Energy poverty has been largely explored in the context of the Global South where barriers to energy access are linked to poor infrastructure as well as low incomes resulting in households relying on wood and other forms of biomass which is strongly associated with health issues. Fuel poverty has been the term used in the United Kingdom and Ireland and is linked to specific causes – low incomes, poor energy efficiency of the housing stock. Table 1 gives an overview of definitions and indicators using in measuring energy poverty in selected EU countries.

Table 1: Definitions and measuring of energy poverty in selected EU countries

|

Member State |

Definition |

Measuring energy poverty |

|

Slovakia |

Energy poverty under Act No. 250/2012 is a status attributed to households when ave¬r¬age monthly household expendi-tures on electricity, gas, heating, and hot water represent a substantial share of the average monthly household income. |

N/A |

|

France |

Energy poverty is attributed to people who encounter diffi-cul¬ties in getting ade-quate energy supply to satisfy basic needs in their dwellings. This is often due to insufficient resources or inadequate hou-sing conditions. |

Three indicators have been proposed but not operationalized: 1) the Energy Effort Rate (EER, or TEE in French) is the ratio between energy ex¬pen¬ses and income of the household, which should not exceed 10%, and refers to the first three income deciles; 2) the LIHE (BRDE in French) is an indicator of energy poverty in a house¬hold if low income and high energy exp¬enditures as condi-tions are met; 3) the so called cold indica¬tor relies on testimo¬nials regarding the level of thermal com¬fort and level of budget constraints. |

|

Ireland |

Energy poverty is a situation whereby a household is unable to attain an accept-able level of energy services (including heating, lighting, etc.) in the home due to an inability to meet these requirements at an affordable cost. |

10% metric – but with higher thresholds to determine the seve¬rity. |

|

Belgium |

Energy poverty is at-tri¬buted to house-holds that spend too high a proportion of their disposable in-come on energy costs. |

Double the median expenditure thres¬hold (equivalized income). Only the lower five income deciles are included. Complemented by depth/hidden pover¬ty metrics. |

|

Hidden energy pover-ty is attributed to households which spend abnormally low amounts on energy services |

Household expendi¬ture is below the me¬di¬an expenditure of households of the same size and type. |

|

|

England |

Fuel poverty is attri-bu¬ted to households for which 1) house-hold incomes are be-low the poverty line (considering energy costs); and 2) their energy costs are high-er than what is typical for their type of house¬hold. |

LIHC + fuel poverty gap. Income is calcu¬la¬ted on an ‘after hou¬sing costs’ basis (deducting mortgage, payments, rent) and equivalized to ac¬count for the house-hold composition. The income threshold is below 60% of the net median income. |

|

Austria |

Energy poverty is at-tri¬buted to house-holds considered as energy poor if their income is below the at-risk-of-poverty threshold and, at the same time, it must cover above-average energy costs. |

LIHC. The at-risk-of-poverty threshold is 60% or less of the median income (equi-valized). Above-ave¬rage costs - either 140% of the median expenses can be con¬sidered above aver¬age or fixed at 167% of the median costs. |

|

Cyprus |

Energy poverty can refer to situations in which consumers find themselves in a diffi-cult position due to their low income as indicated on their tax statements and in con¬junction with their professional sta¬tus, marital status, and specific health conditions and there-fore, they are unable to cover the costs for adequate electricity supplies, given that these costs represent a significant propor-tion of their disposa-ble income. |

N/A |

|

Scotland |

Fuel poverty is attri-bu¬ted to house¬holds which, in order to main¬tain a satisfac¬to-ry heating regime, are forced to spend more than 10% of their in¬come (inclu-ding the official Hou-sing Bene¬fit or In-come Support for Mort¬gage Inte¬rest) on all household fuel use. |

A satisfactory heating regime, as recom¬men-ded by the World Health Organization, is 23°C in the living room and 18°C in other rooms, and is to be maintained for 16 hours over every 24-hour period in households with older people or peo¬ple with disabi¬lities or chronic illness, and at 21°C in the living room and 18°C in other rooms for a period of nine hours over every 24-hour period (or 16 hours over 24 hours on weekends) for other households. |

|

Wales |

Fuel poverty is defi-ned as having to spend more than 10% of income (including housing benefits) on all household fuel used to maintain a satisfactory heating regime. Expenditure on all household fuel exceeding 20% of in-come means that households are defi-ned as suffering from severe fuel poverty. |

10% metric. Satisfactory heating regime – as above. |

|

Northern Ireland |

A household experi-en¬ces fuel poverty if, in order to maintain an acceptable tempe-rature level through-out the home, the occupants are forced to spend more than 10% of their income on all household fuel use. |

10% metric. Satisfactory heating regime – as above. |

Source: Directorate General for Internal policies, Policy Department C: Citizens’ rights and constitutional affairs, “Gender perspective on access to energy in the EU.” 2017.

Conclusion

Energy poverty is driven by many factors such as low income, low energy efficiency of dwellings, climate, availability of energy sources and energy prices, to name just a few. The main drivers of energy poverty also include macroeconomic development, final energy consumption of households, the availability of different energy sources, energy prices, housing efficiency, climate.

However, detection and quantification of energy poverty is a complex and challenging task. There are three main reasons for this:

- Energy poverty is a private problem – it is largely confined to the walls of the home and is not easy to observe or follow from a public policy standpoint.

- Energy poverty varies over time as house-hold circumstances change, manifesting diffe¬rently in various geographical settings – every measurement is a ‘snapshot’ and may not adequately represent the entirety of circumstances faced by vulnerable house-holds.

- Judging the level of energy services received in the home is a matter of individual percep¬tions and preferences, which themselves are dependent on social and cultural expecta¬tions. For example, a home that might be con¬sidered well-lit and warm by one indivi¬dual may not be seen as such by another, especially if the two come from different backgrounds or live-in different countries.

So, to conclude, measuring and monitoring energy poverty is not an easy task. It includes specificity of every single country and depends on facts that are not easy to measure. Nevertheless, some countries succeed to define and measure indicators of energy poverty which is presented in the policy brief.

Main source of information: Study on Addressing Energy Poverty in the Energy Community Contracting Parties, EIHP, DOOR, (ECS, 2021).